http://xa.yimg.com/kq/groups/1853519/1538570472/name/Review+of+BAMBOOS+OF+TBGRI+by+Wong+(2011).pdf

Gardens’ Bulletin Singapore 62 (2): 337–338. 2011 337

Gardens’ Bulletin Singapore 62 (2): 337–338. 2011 337

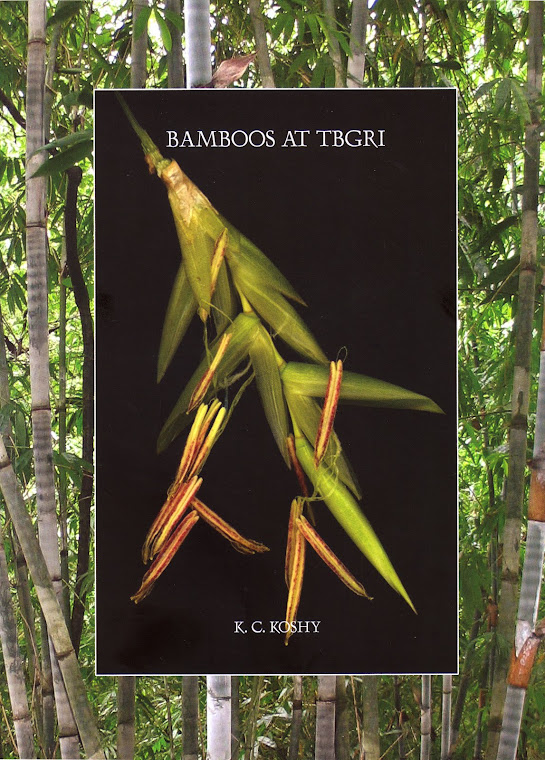

BOOK REVIEW. Bamboos at TBGRI. K.C. Koshy. 2010.

Thiruvananthapuram, Kerala, India: Tropical Botanic Garden and Research Institute. 27.5 cm × 19.8 cm, card cover. 104 p. Price Rs. 800 / US$ 30.

“All botanic gardens keep records of their living collections.” Thus declares the opening sentence in the preface to this book by Dr. K.C. Koshy, the founder of the Bambusetum at the Tropical Botanic Garden and Research Institute (TBGRI) in Kerala, India. That exhortation does not detail how well those records should be kept, and Koshy proceeds to show how.

This account was well-conceived, at a time when the TBGRI bamboo collection has just entered its third decade with nearly 70 species (currently recognised as 15 genera) and more than ten putative hybrids making up a whopping 933 accessions, a very good stage at which to declare coming of age. The opening chapter sets the foundation of the Bambusetum in the context of TBGRI’s history. Beginning with a mere 0.5 ha at inception, this Bambusetum has now grown to occupy nearly 6.6 ha (just more than 16 acres) in the sprawling green 121-ha campus of the TBGRI. Koshy gives a quick overview of Asian and Indian bambuseta, drawing attention to the humble beginnings of those collections that today continue to support scientific studies, such as at the East India Company (later Indian) Botanic Garden at Howrah, Calcutta from the time of Roxburgh in the early 19th century, as well as a good number of newer collections established around the 1980s. Notes are provided on the propagation methods used at TBGRI, the stage-by-stage development, and the geographical provenances covered that emphasised the Western Ghats region and North Western and North Eastern India. Koshy also documents how thirteen taxa were duplicated from the bambusetum of the Forest Research Institute at Dehra Dun, where specialist attention for bamboo taxonomy and genetics, biology and utilisation, have been and continue to be emphasised. This kind of duplication represents some insurance against loss at one location and also allows comparative studies in different environments. One or two anecdotes, such as the difficulties of transporting bulky plant offsets by passenger train, the Manipur collecting expedition through insurgency areas, or the monsoonal damage to Bambusetum plants in June 2003 that had to be dealt with, make the account come alive. Building a bambusetum is not just planting bamboo, it brings us into contact with much else, and often in ‘heavyweight’ fashion.

The main records are compiled as Chapter 2. Herbarium and spirit-preserved material help document the living accessions. The entries are organised by genus and species in alphabetical order. Each taxon entry provides the scientific name, relevant taxonomic references, a brief description of the species, a literature-based distribution statement, and a note on the number of hereditary lines represented by the TBGRI material. The accession numbers of the taxon are given with location statement and (presumably GPS) coordinates in the TBGRI Bambusetum; planting date; propagule type used; details of origin (typically state, district and precise location), collection date, and collector and collection number. Herbarium and spirit collections associated with the material (either collected from outside the Bambusetum, or within: this is carefully distinguished) are also given when available. But not only are there planted bamboo accessions in the Bambusetum, as two natural populations, Bambusa bambos and Ochlandra travancorica, have been carefully conserved on site.

This book is very nicely produced, replete with end-paper photographic spreads of Pseudoxytenanthera bourdillonii (Gamble) H.B.Naithani and a frontispiece with an alluring teaser in the form of an unidentified gigantic Dendrocalamus sp. Nearly every page has full-colour photographs, and there are a good number of full-page photographic reproductions (a Roxburgh painting of Melocanna baccifera faces the Preface), including many of the Bambusetum accessions. A contour map of the TBGRI Bambusetum showing the locations of all accessions spans nearly two pages, which means a serious fold is found right across it, and the fine print used for accession numbers on this map can be a challenge to the reader. Apart from this, the book is a highly unusual, but extremely welcome, detailed (and pleasant-to-consult) record of a scientific collection of living bamboos. It is unprecedented.

The TBGRI is a young institution, set up in 1979, and its Bambusetum was established in 1987, so it could be surprising that, in effect, this book unveils to the modern world one of the finest, if not the best, scientific living collections of bamboo in all of India and the tropics. And K.C. Koshy, certainly, has set the standard for not only TBGRI, which looks towards an ever-increasing role in tropical plant research,but any institute that seriously wishes to build a scientific collection of bamboos. TBGRI has had the ‘right recipe’: forefathers with good breadth of vision, passionate researchers who are well-qualified and dedicated to the task, good networking, and the great Kerala setting for tropical plants. It had worked before in the tropics and works again.

K.M. Wong

Singapore Botanic Gardens

No comments:

Post a Comment