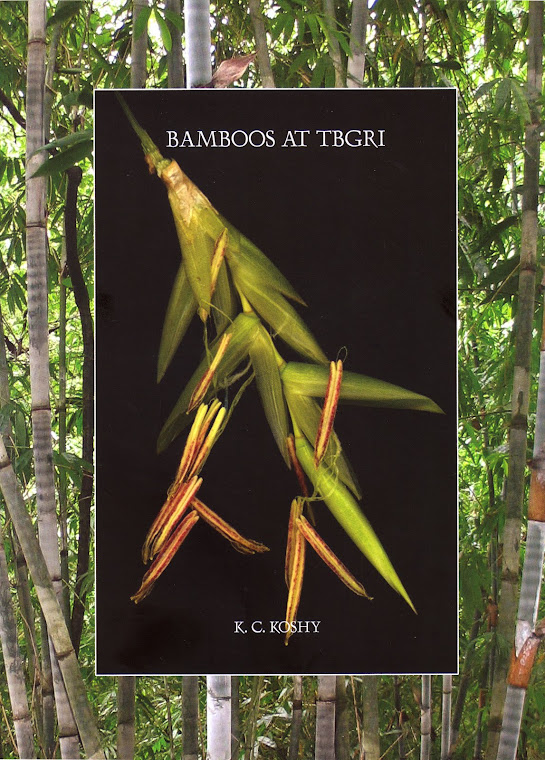

Bamboos at TBGRI.

Koshy, K.C.2010. ISBN 978-81-920098-0-3 (paperback) 104 pp. Tropical Botanic Garden Kerala , India

This is a wonderful book on a developing bambusetum, a living collection of bamboo species. The site is part of the Tropical Botanic Garden Kerala , India Ghat Mountains

Koshy tells the story of the project in a straightforward fashion, discussing the obstacles encountered and the successes achieved. He notes the advantages of a bambusetum: the accessibility of a collection for scientific study including the flowering cycle, the availability of material for farmers or foresters, and the possibility of studying the other species which form communities with bamboo. He also describes bamboo-collecting expeditions and their fruits.

Among other notes on these plants, Koshy makes clear the major hurdle to studying bamboos: they flower very rarely, and in many cases only once in a life cycle. Since the vegetative forms of many species look very similar to each other, it was difficult for Koshy to even know how many species he had, particularly at the early stages of the project. In addition, such infrequent flowering makes it not easy to create hybrids, though his team has managed to produce twelve, which are all listed here.

Also included are short discussions about the roles a number of botanists played in developing the collection. There is even a short section on the VIPs who have visited the bambusetum, including Ghillian Prance, then Director of the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew .

Following this introductory material, Koshy then presents the heart of the book, an annotated list of the bamboos species at TBGRI. Many of the descriptions, which include information both on the living plants and herbarium specimens, are accompanied by photographs. There are data here on when the plants were accessioned, on flowering if known, and statistics on length of internodes and the size of leaves. These descriptions are brief and are presented more as lists than narratives.However, they would be useful to those studying bamboos and having some knowledge of the family.

After this section, which takes up about three quarters of the book, there is information about the TBGRI’s bamboo museum and about its nursery. The book ends with a discussion of future plans as well as a list of references, and finally an index to bamboo scientific names.

This 104-page paperback is beautifully produced with many photographs, including a number of full-page ones showing close-ups of particular species as well as views of the TBGRI. The volume was obviously a labor of love for Koshy and for the Garden. It is not a general introduction to bamboos, but it would be a shame if it were missed by someone seeking to learn more about these plants. The introductory material as well as the explanations of how hybrids were developed provide excellent general descriptions. The detailed information on each species would be interesting to an expert, and in the years ahead it will serve as documentation for what this bambusetum held at a particular moment in its history.

-Maura Flannery, Department of Biology, St. John’s

www.botany.org/PlantScienceBulletin/psb-2011-57-3.pdf

www.botany.org/PlantScienceBulletin/psb-2011-57-3.pdf